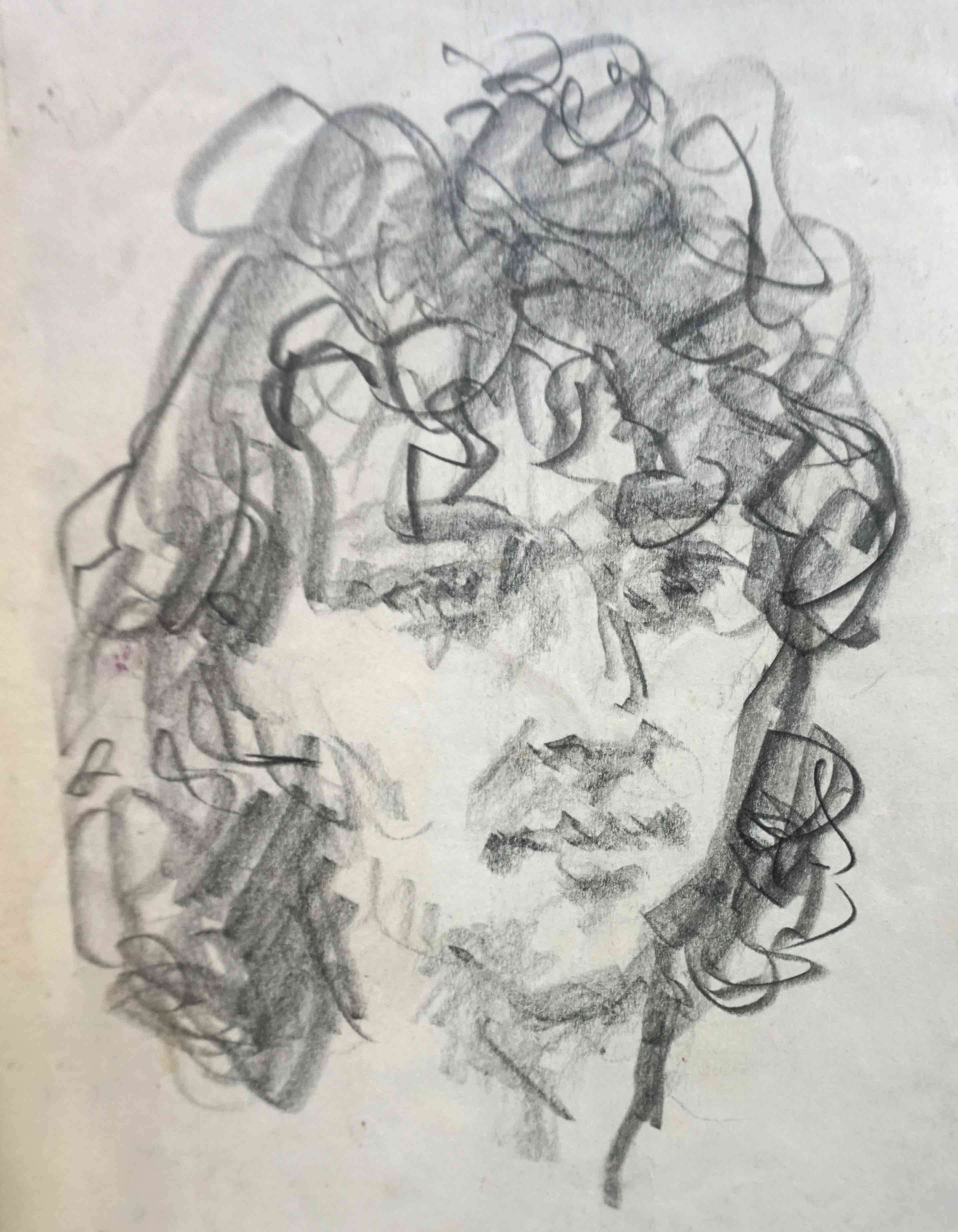

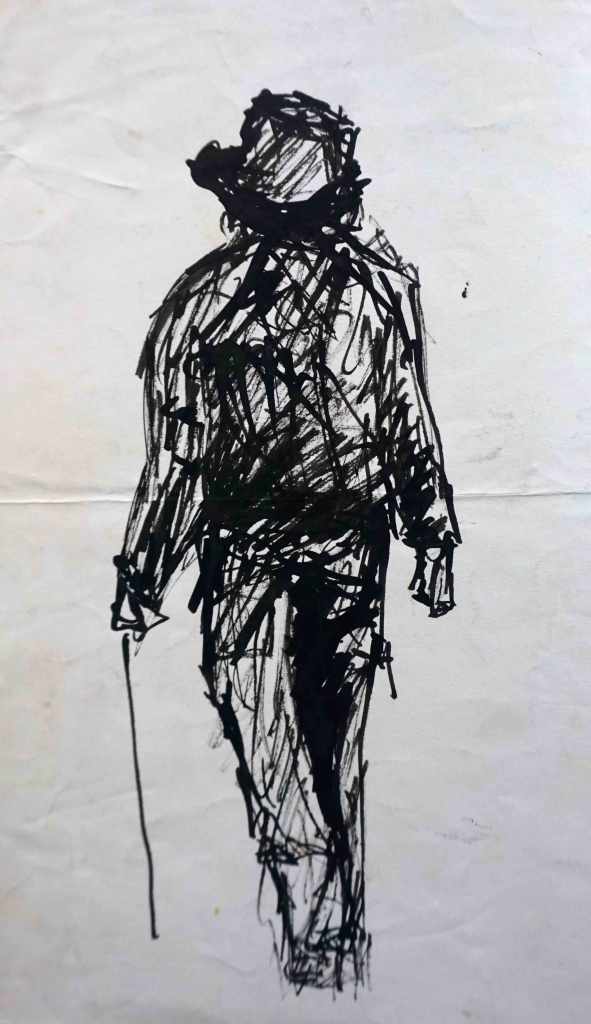

The mixed media art of Christophe Demaître places itself on the fragile boundary between painting, photography, and even sculpture. His works are imbedded with the dual perspective of the “painter-photographer”. He achieves this by superimposing photographic silver emulsions on an array of materials reminiscent of the “Arte Povera” movement, ranging from the classic canvas to fabric, wood or metal. The artist’s style reflects on the alternation between the patience of the photographic research in obtaining the best visual result, and the impulsive creativity with which the painter completes the work of art. The result is a poetical yet alienating essay of Demaître’s favorite source of inspiration – the urban environment.

Galileo’s ambition pushed him to go further, and in the fall of 1609 he made the fateful decision to turn his telescope toward the heavens. Using his telescope to explore the universe, Galileo observed the moon and found Venus had phases like the moon, proving it rotated around the sun, which refuted the Aristotelian doctrine that the Earth was the center of the universe.

Walter Benjamin’s 1935 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” situates art within a larger socioeconomic context. He notes that as long as humans have been making art, they’ve also been copying it—printing, retracing in a master’s style, or reusing the same sculptural molds. Yet in the modern age, photography and film could capture the world better than any traditional art form. Then why are painting and sculpture still worthwhile? Benjamin suggests that what truly makes an original artwork special is intangible. “Even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art,” he writes, “is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be.” After Benjamin, it’s difficult not to connect an artwork to the larger system in which it operates.